I. Introduction

In requirements engineering, a goal model is used for specifying the requirements of a software system in terms of the intentions of various stakeholders. A goal model consists of top-level goals that are decomposed into subgoals and tasks, with the relationships between these elements indicated with links connecting them. A goal model can be implemented using the i* modelling language [1].

There are simple analysis techniques that use these i* models to help stakeholders make decisions which best lead to the satisfaction of their goals. One such technique is forward analysis, where discrete values such as satisfied, denied and unknown are assigned to the leaf-level goals and tasks in the model [2]. These values can then be propagated up the tree to determine the satisfaction of the higher-level goals.

While useful, this technique is limited when attempting to answer questions about how best to satisfy goals in the model, as the satisfaction values are constant after being assigned. This assumption that the values will not change overtime is not an accurate representation of the real world, where both the requirements of a system and the environment it exists in can frequently change. Reasoning using these models might lead to design decisions which are not the best in the long run.

For example, if a modeller wished to know if their design would still be functioning over a multi-year period of time, standard analysis techniques might only show whether the design is satisfactory under present conditions. This could lead them to a design decision that would not satisfy all of the requirements over a longer period of time.

A method has been proposed to account for this dynamic behaviour by supplementing the i* language with temporal functions in the model [3]. Instead of using the static values of satisfied, denied, and unknown, we represent the satisfaction value of goals and tasks as discrete functions over time. These functions take discrete time points as inputs and output the satisfaction value of the goal at that time. This extends the analysis technique detailed above with a simulation. As the simulation runs through the time points, the model is updated at each point to reflect all of the satisfaction values for that time.

In order to test the viability of this method, a tool is needed for users to visually create models, and run the simulation on them.

II. Approach

An examination of five existing i* goal modelling tools revealed that they were insufficient for this technique. As they were designed with a different intent, they are not easily extensible. Additionally, the tools took time to learn and required installing supporting software, so users would need to be motivated to use them.

To mitigate this, we decided to create a web-based tool. This tool would run in a common browser and only require Javascript. Specifically, we used the JointJS diagramming library [4] as the platform to build the tool on top of. The tool, which runs on an Apache web server, runs Javascript on the client side to reduce the computation and eliminate the storage necessary on the server side. In order to run the simulation, the data is sent to our server to be processed. This is a one-time computation and does not require us to store any long-term data about the models.

The focus in the design was for the tool to be intuitive and usable with minimal instruction. The tool uses a drag-and-drop interface, so users can simply drag elements such as goals and tasks from the stencil onto the canvas to create their models. Features added to increase the usability of the tool include copy and paste, undo and the ability for users to save and load models. The simulation can be run at any point during the modelling, and allows the user to scroll through the timeline and view the model at any particular point in time.

III. Analysis

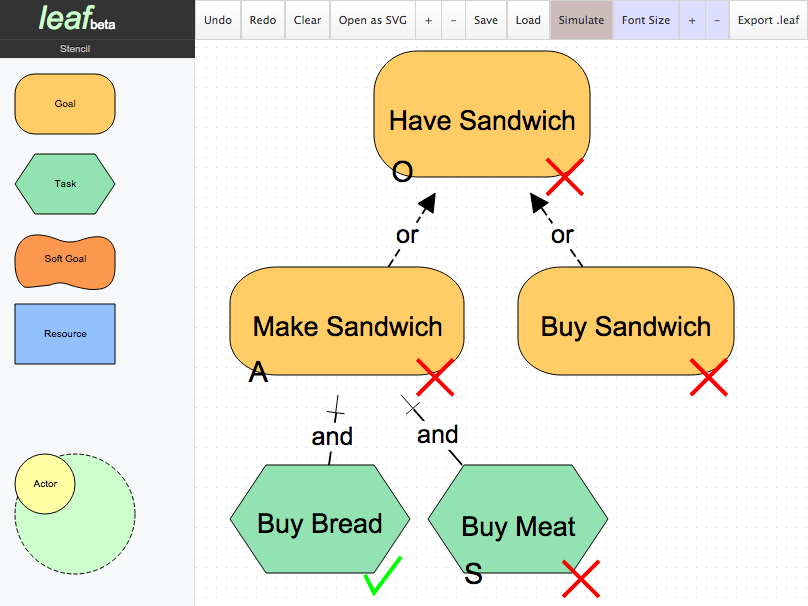

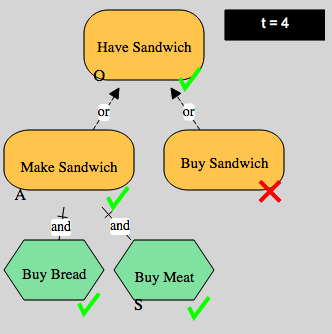

Figure 1 shows a simple model created in the tool. In the original model, the goal “Have Sandwich” is unsatisfied as the denied values propagate up the model. However, the task “Buy Meat” is associated with a Set-Stay-Set Positive function, which means its value will change over time to satisfied and remain that way. One frame of the simulation is shown in Figure 2. The value of the “Buy Meat” goal has become satisfied, and so the satisfaction has propagated up the tree and resulted in our main goal of “Have Sandwich” being satisfied. Notice how the satisfied value on the “Buy Meat” task has propagated to the “Have Sandwich” goal.

We have used the tool to build medium-sized goal models containing around 20 goals, tasks and subgoals. We have conducted preliminary interviews with five goal modelling experts and have used their feedback to refine the interface and improve the functionality of the tool.

IV. Conclusion

In this project, we built an intuitive tool to add dynamic, time-based considerations to i* goal modelling. The purpose was to allow users to account for changes over time in order to make more informed decisions when reasoning with their models. Work is ongoing to further extend i* and develop further tools in order to give modellers more information to better reason with their goal models and ultimately lead to better design decisions. We are currently planning a user study to evaluate the effectiveness and intuitiveness of the tool with a broader audience.

References

[1] E. Yu, “Towards Modeling and Reasoning Support for Early-Phase Requirements Engineering,” in Proc. of rE’97, 1997, pp. 226–235.

[2] J. Horkoff and E. Yu, “Interactive Analysis of Agent-Goal Models in Enterprise Modeling,” Int. J. of Inform. Syst., vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 1–23, 2010.

[3] A. M. Grubb, “Adding temporal intention dynamics to goal modeling: A position paper,” in MiSE’15, 2015.

[4] clientIO, “JointjS.” 2015.