1 Introduction

Writing a correct computer program can be both difficult and tedious. To simplify the work of software developers, program synthesizers are used to aid with this. Synthesizers are themselves programs that automatically generate programs for developers based on some specifications. Previously, researchers have used syntactic guided methods for synthesizing programs whereby a rough skeleton of the program code—a syntactic template—is provided by a user to aid in finding a correct program. Unfortunately, in many practical cases it is hard for a user to provide a template [1]. We introduce a method for automated program synthesis, where the synthesis algorithm generates a program through an iterative process. For the purpose of this project, the specification consists of a precondition, a postcondition, and a list of program statements.

2 Background

A trace is a sequence of program statements in the order that they are executed in a program run. A program can be represented as a set of traces; together these traces represent all possible executions of that program. Moreover, a trace is correct if and only if assuming the precondition, the program variables satisfy the postcondition after the execution of the trace.

In order to verify the correctness of a program, there are two important properties that need to be checked, safety and liveness. A program satisfies the safety property if all traces of the program are correct. A program satisfies the liveness property if the program eventually terminates for all possible inputs.

We denote the set of programs by $\mathscr{L}(P)$. A program is well-formed if the program is constructed according to the syntax rules. $\mathscr{L}(P)$ is constructed to only represent the sets of traces that are well-formed programs. In simplified terms, a set of traces is a well-formed program if a syntactically valid program can be constructed from the set of traces.

Another important concept in our approach is the representation of correct programs. We denote the set of correct traces $\Pi$. From $\Pi$, we use power set construction described in [3] to compute $\mathscr{P}(\Pi)$, the power set of $\Pi$. $\mathscr{P}(\Pi)$ consists of all subsets of the traces in $\Pi$. If a program whose set of all possible executions is a set of traces in $\mathscr{P}(\Pi)$, then that program must be safe because every trace of that program is also in $\Pi$ by definition. However, not every set of traces in $\mathscr{P}(\Pi)$ is a well-formed program. We also define the set $\Omega$ to contain the set of all terminating traces which can intuitively be grouped to form a terminating program.

3 Approach

We use a counterexample Guided Abstraction Refinement or CEGAR loop approach as first described in [2], where we take counterexamples — in the form of a trace — and generalize from them to improve our proofs. Generalizing a trace involves deriving similar traces which are correct for the same reason as the given trace is. We will first show our methods for synthesizing safe programs. Next, we will shows ways in which our methods can be extended to synthesize safe and terminating programs.

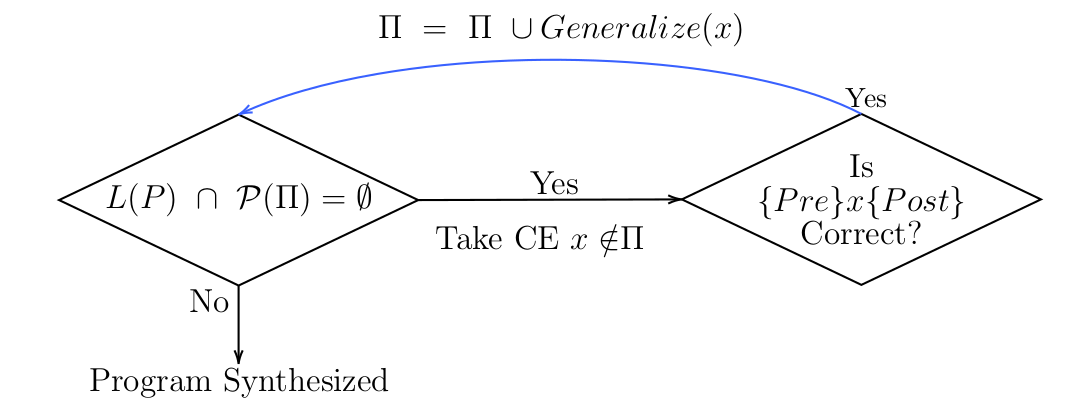

To synthesize safe programs, we need to find correct traces until the algorithm finds a program that is well-formed and satisfies the safety property. To find correct traces, we take a set of traces in $\overline{\Pi}$, which consist of traces whose correctness is unknown, as counterexamples. Then, using Satisfiability Modulo Theorems or SMT solver, we generate interpolants from the counterexamples and generalize $\Pi$ from the interpolants [5]. Next, we compute $\mathscr{L}(P)\cap\mathscr{P}(\Pi)$, which contains only sets of traces that are safe, well-formed programs, and check its emptiness [6]. In the case that $\mathscr{L}(P)\cap\mathscr{P}(\Pi)$ is empty, more counterexamples are taken from $\overline{\Pi}$, and interpolants are computed from them to generalize $\Pi$ until $\mathscr{L}(P)\cap\mathscr{P}(\Pi)$ is no longer empty, in which case a safe program can be extracted from $\mathscr{L}(P)\cap\mathscr{P}(\Pi)$. This concept is illustrated in Figure 1. In the diagram below, $CE$ denotes counterexample.

Figure 1: The CEGAR loop for synthesizing safe programs.

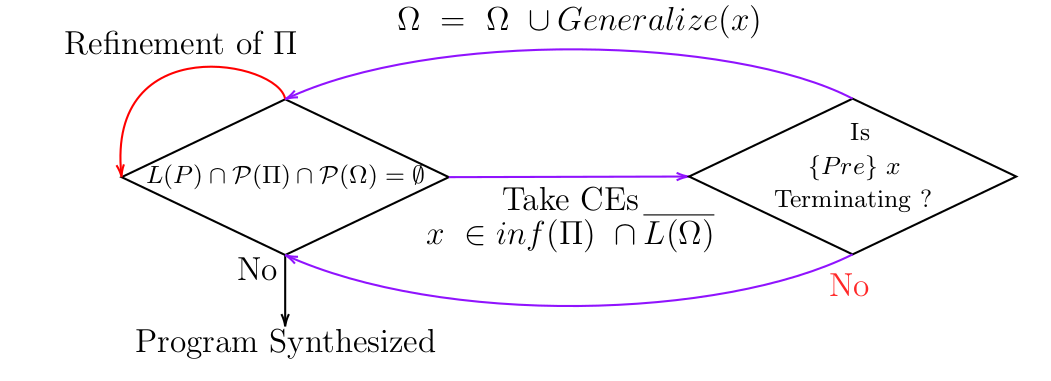

Figure 2: The CEGAR loop for synthesizing programs that satisfy the liveness and safety properties.

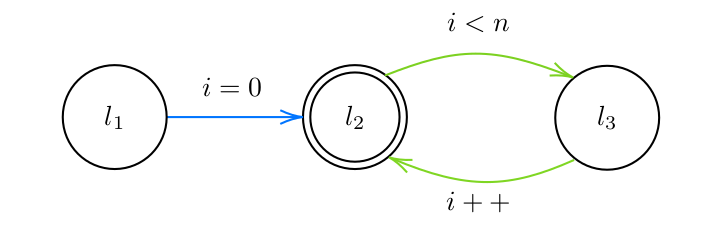

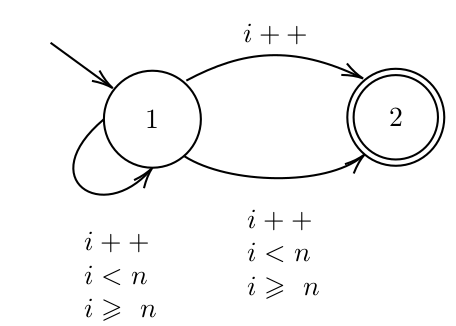

To ensure the generated program also satisfies the liveness property, the approach simultaneously shows that there is a non-empty set of terminating traces. As defined earlier, this set will be denoted by $\Omega$. $\Omega$ is modified using a similar CEGAR approach as was used for generating programs that satisfy the safety property. In this modified approach, counterexamples are taken from the set which is the intersection of the traces in $inf(\Pi)$ and the traces which have not already been added to $\Omega$, expressed as $\overline{L(\Omega)}$. The traces in $inf(\Pi)$ are traces whose prefixes have correct extensions in $\Pi$. On the other hand, the traces in the set $\overline{L(\Omega)}$ are traces which have not been verified to be terminating yet. Then the traces in the intersected set, $inf(\Pi) \cap \overline{L(\Omega)}$, are counterexamples which are correct extensions to their prefixes, and ones that have not been analyzed for termination. The analysis of these traces is explained bellow. An example of these traces is shown in Figure 3. The automaton in the diagram will accept any trace that increments $i$ as long as $i<n$, and the trace must be finitely long since eventually, $i$ will be greater or equal to $n$.

Figure 3: An infinite counterexample.

To verify the termination of these unchecked counterexamples, a method described in [4] is used. Terminating counterexamples are added to $\Omega$, along with their generalized counterexamples. The purpose of generalizing traces in $\Omega$ is to add additional traces to $\Omega$ which are also terminating. These traces are terminating for the same reason that the counterexamples of interest were in the termination analysis.

To synthesize a terminating program, the terminating traces in $\Omega$, are grouped together into combinations of traces. As described earlier, $\mathscr{L}(P) \cap \mathscr{P}(\Pi)$ is the set of well-formed programs which are correct. In processes of generating a program which also terminates, the set of terminating programs $P(\Omega)$, is also intersected with the two sets. This way, if the overall set is non-empty, then there is a well-formed program which is correct and terminating. This process can been seen in Figure 2.

4 Analysis

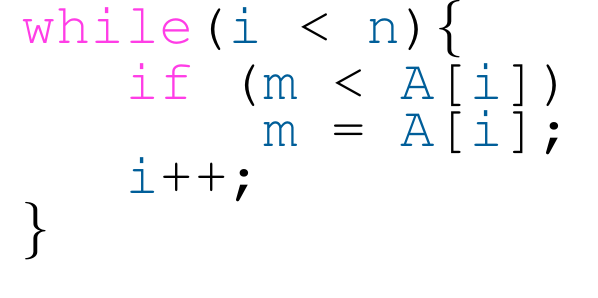

First, we consider a special case of synthesis known as verification. This involves taking a program, along with encodings of a set of pre-conditions and post-conditions, and verifying that this program satisfies both of those sets. In this special case, $\mathscr{L}(P)$ contains a single program. Our goal is to verify the safety property of the program using our synthesis loop. We believe the worst-case time complexity for our algorithm is in NP, but We are able to verify in 560s that the program in Figure 4 indeed finds the largest element in an array.

Figure 4: A program that finds the largest element in the array A.

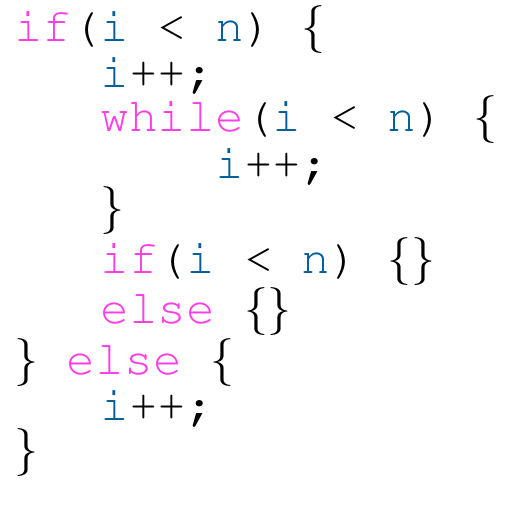

Next, using the loop in Figure 2, we attempt to synthesize a terminating program that increments the variable $i$ until $i$ equals to the variable $n$. However, the generalization procedure for $\Omega$ is not functioning as intended so, instead, the set of traces represented by the automaton in Figure 5a is passed in as $\Omega$. Eventually, the program in Figure 5b is synthesized in 382s, but we believe the worst-case time complexity for this algorithm is also in NP.

Figure 5

(a) A representation of infinite traces that must eventually terminate.

(b) A synthesized program that increases i until i reaches n. i is initially 0 and n is greater than 0.

5 Conclusion

Automated programming tools will be an invaluable tool to programmers in the future. Unfortunately, as outlined in the analysis, these methods seem wildly slow even for trivial algorithms. The complexity of most of the set operations as well as the generalization operations lead to an exponential or worse blow up in complexity. As a result, the development of efficient algorithms for each of these tasks will be vital if progress is to be made on improving the CEGAR synthesis approach.

References

-

Allessandro Abate et al. “Counterexample guided inductive synthesis modulo theories”, In Computer Aided Verification. H. Chockler and G. Weissenbacher, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. pp.270-288.

-

E. Clarke, O. Grumberg, S. Jha, Y. Lu, H. Veith, “Counterexample-Guided Abstraction Refinement”, in Computer Aided Verification. E. A. Emerson and A. P. Sistla, Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2000. pp.154-169.

-

Azadeh Farzan and Anthony Vandikas. “Automated Hypersafety Verification”, in Computer Aided Verification. I. Dillig and S. Tasiran, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019. pp.200-218.

-

M. Heizmann, H. Jochen, P. Andreas., “Termination Analysis by Learning Terminating Programs”, in Computer Aided Verification, A. Biere and R. Bloem, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2014. pp. 797-813.

-

M. Heizmann, J. Hoenicke, and A. Podelski., “Refinement of Trace Abstraction”, in Static Analysis. J. Palsberg and Z. Su, Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009. 2009. pp. 69-85.

-

Moshe Y. Vardi and Pierre Wolper, “Automata-Theoretic Techniques for Modal Logics of Programs”, Journal of Computer and System Sciences, vol. 32, pp. 183-221, 1986.